Joined-up value-chain thinking (en)

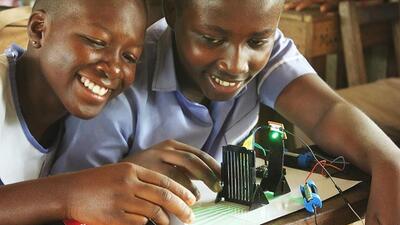

Approximately four million people in developing countries move from rural areas to live in cities every week. While living in rural locations, these people had access to supplies of basic fresh produce of some sort in a local market or from family smallholdings. As they move to the city, however, they lose that source of supply of fresh produce.

Distribution chains from rural food production areas to cities tend to be poorly organized and suffer from a lack of investment. In most developing countries more than 50% of food grown is wasted before it reaches markets. Investment in post-harvest conditioning and value addition (appropriate technology for drying, freezing, chilling, packaging) and facilities to keep food fresh and nutritious along distribution chains to the point of consumption are missing from many cities. A study released this week from the UK Institute of Mechanical Engineers covering a number of cities in developing countries shows that after purchase around 30% of food is thrown away by consumers, unused.

We know from previous studies (e.g. McKinsey: “Profit at the bottom of the pyramid”, November 2009 and “Winning the Indian Consumer”, September 2005”) that small scale-retail outlets in developing country cities achieve higher unit prices for food than supermarkets in more competitive areas of Europe and North America. This fact is driving large global food and consumer goods companies such as Unilever, Walmart and ShopRite to innovate in distribution channels and approaches to corner stores and mobile distributors in countries like Bangladesh, India and Nigeria. The interest of these large multinationals in such markets shows how remunerative they can be with the right organisation and scale.

Feeding growing urban communities at all levels of wealth with healthy nutritious food may sound challenging but offers a tremendous opportunity for intra-regional trade if a number of policy and practical factors holding up such development can be addressed with what I call “joined-up value chain thinking”. The question is how can such thinking be turned into positive, coordinated action on the ground?

Some of the challenges became clearly visible to policymakers during the food crises of 2004 and 2008-2009 as urban communities took to the streets to protest. Governments that reacted by stopping exports of produce may have solved a short-term problem but also caused food prices to rise and put suppliers with long-term export contracts in default.

Only recently have initiatives started to build infrastructure and cross-border protocols between African countries as trading partners. A large number of non-tariff measures (NTMs) in areas such as plant-pest control, health and food safety are not yet harmonized between neighbouring states. One result, for example, is that there may be counter-seasonal demand for agri-food products north and south of the equator in, for example, East Africa, but few transport linkages or equipped border-crossing points to allow an efficient flow of food products without excessive spoilage. This means that seasonal deficiencies in one region cannot automatically be replenished from another climate zone in the same region. Many initiatives and goodwill gestures have been started but how can regional bodies accelerate improvements in the integration and performance of supply chains?

Instead of focusing on reducing waste and cooperating on improving technology along supply chains the developed world seems to want to concentrate on increasing productivity and imposing more and more exacting “standards” that increase costs for suppliers – shifting the burden up the chain to those least able to afford it.

ITC has worked for many years on delivering holistic market-led development solutions for the agri-food sector along value chains. It also pioneered a methodology for inclusive participatory design of market-led value chain development strategies that attempt to address the above issues with beneficiaries, civil society, policymakers and implementation agencies together to develop pragmatic solutions. However, along with beneficiaries we are often then frustrated by a gap in support for implementation, particularly in the medium scale financing of small enterprises and communities to upgrade their facilities. This kind of financing is difficult to obtain through normal commercial markets. Large amounts of funding are being targeted at food sectors but gains in one area alone will not solve the overall problem – a balanced approach along whole supply chains fork to farm is required. What will it take to convince more donors and grant-making institutions to offer funding for well-coordinated combined projects bringing together actions in the enabling environment, trade technical assistance and infrastructure projects focused on intra-regional market led food sector development?

The words, ideas and opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the International Trade Centre or any of its partners or donors.

This article was first published on The Broker.